‘Paddy Joe’ (1895-1960): a tribute to a 1916 fighter

INTRODUCTION:

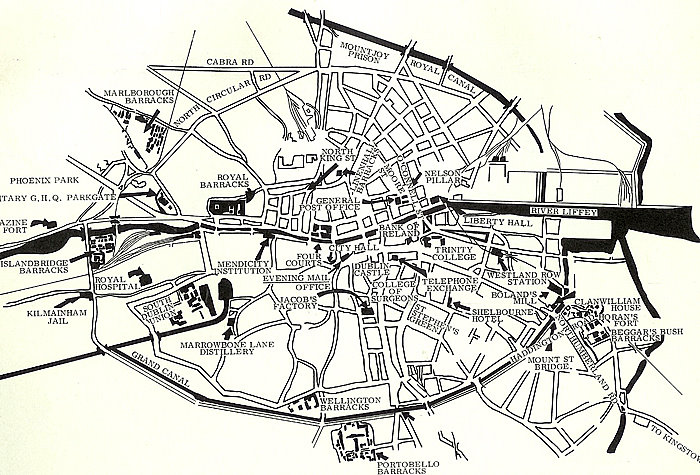

Heuston’s Fort is Paddy Joe’s account of the Fight at the Mendicity in Easter Week 1916, and was written over a number of years, in copious handwritten and typed notes, but not published.

In 1966 my Father, Patrick Heuston Stephenson, (‘Paddy’), edited, and privately published the story for family and friends, supported by his brothers. They decided to publish the story on the 50th Anniversary of the Rising in 1966, and to mark Paddy Joe’s part in it, the publication was also lodged with the National Library, National Museum, and Military Archives at the Curragh.

Paddy Joe’s account of the fight at the Mendicity Institute was used by Desmond Ryan in his book ‘The Rising’. Ryan was James Connolly’s, and Patrick Pearse’s biographer, and a student at St Endas (I have included a copy of Ryan’s book, pages 155-163.) Paddy Joe’s role is also featured in the book by Sean Heuston’s biographer and brother, Fr. J.J. Heuston in his Book ‘The Mendicity Garrison 1916’ (from which I have also included extracts. The handwritten notes are Paddy’s)

Paddy Joe also took part in a Radio Eireann broadcast about the Rising in 1955, and I have included a transcript of his contribution. Paddy Joe’s youngest son Sam obtained wax record copies of the programme which means that Paddy Joe can still be heard talking about the Mendicity Garrisons fight.

The Mendicity Institute was demolished in the early 1970’s and photographs are hard to come by. I have included two: the long shot with the Liffey in the foreground is a 1950’s picture which shows a building quite large for just a few dozen young men to defend, and the frontage shot was in Paddy Joe’s papers and unfortunately in very poor condition.

Jim Stephenson

DEDICATION:

To all the members of the Mendicity garrison, living and dead, and to their gallant leader, Sean Heuston.

`... Never had man or woman a grander cause, never was a cause more grandly served ...'

James Connolly

28th April 1916

FOREWORD:

It seemed appropriate to his sons that the following memoir of his experiences during the Easter Rising, written by the late P. J. Stephenson some few years after the event, should be made available for private circulation to his family and friends during this year of celebration of the fiftieth anniversary of Easter Week.

There were less than thirty men in the Mendicity Garrison. This is a record of events there as seen by one of them, and is dedicated with pride and respect to the entire garrison.

Patrick

Daniel

Desmond

Noel

Samuel Stephenson

April 1966

Part 1: PRELUDE

Shortly after leaving the Christian Brothers Schools, North Richmond Street, in the summer of 1910, I was brought into the movement for national independence when I was enrolled a member of the McHale Branch of the Gaelic League, then meeting at 91 Upper Dorset Street, by my elder brother Sam who was then working as a Muinteor Taisteal. Sam had gone as far as Senior grade in the National System of Education, and having learned Irish from the Christian Brothers had studied in the Leinster College of Irish and so on to his bicycle to join that band of enthusiasts who went round Ireland spreading the new gospel of Irish Nationality. By attending at Feisanna, Ceilidthe, Sheligs, the Aonach and the Oireachtas, I came to know most of that unique band of heroic men who were to write the most glorious pages in the history of Dublin and of Ireland. As a Dubliner there was little I could be proud of in the history of my native city, which up to 1913 had for the most part been the centre of British Imperial oppression in Ireland. In 1912, after trying my hand at being a brush-maker and later a stationer, I entered the Dublin Corporation as a library assistant, intending to study and sit for the Corporation Clerkship examination. Being engaged in my free time in working for the examination I did not join the Irish Volunteers on their foundation in 1913. I was on late duty in the Thomas Street library the night of their foundation in the Rink in Rotunda Gardens and so missed taking part in that famous event, and I missed being part of the historic Howth gun-running as well. Although attending Bonser's Commercial College in Harcourt Street to study for the Corporation examination, the teaching of Irish in the McHale Branch kept me a little more in touch with events. The failure of my first attempt at the Corporation examination and my consequent discouragement and decision to quit studying left me with some free time on my hands. This along with the effect of the split in the Volunteers, and the continued sight of my friends and acquaintances marching and drilling proved irresistible and one evening early in 1914 I went to No.5 Blackhall Street, the Colmcille Branch of the Gaelic League, and joined D Company of the 1st Battalion of the Irish Volunteers. To my great surprise the Captain turned out to be Sean Heuston whom I had last seen in O'Connell Schools, North Richmond Street, some eleven years before. To my even greater surprise I was ordered abruptly to fall in with the other members of the Company - just as if we had never met before. A little peeved at my reception I made up my mind to show I was as good as the next fellow, and executed smartly and correctly all the Company drill through which Section Leader, Dick Balfe put us that evening. Fortunately the physical drill and training which was part of the curriculum in Richmond Street came to my aid, and I made no mistakes. My reward came when after the dismiss I went up to Dick Balfe to offer him out of my half a crown a week pocket money a subscription for a rifle. Dick, surprised at what seemed to him unusual keenness for a recruit, called Sean over to comment on this phenomenon. He must have had me under observation during the parade for ignoring Dick's remarks he asked me how I was so good at the foot drill. When I told him I had learned it at Richmond Street, he smiled and said "Now I remember, I was wondering where I had seen you before." The abrupt efficient officer became a cordial human being and after a few minutes chatting he went away with Dick. I left that night full, for the first time in my long life of twenty years, of a sense of belonging to something worthwhile, and enjoying a sense of well-being, which later I was to understand derived from that quality of leadership and greatness that Sean and his like possessed, and which they communicated to those they commanded. As a Gaelic Leaguer I was no stranger in Colmcille, so I was soon at home there and with the other members of the Company. The Battalion Commandant, Ned Daly, I already knew as he had been a frequent visitor to the McHale Branch along with the Battalion Adjutant Sullivan and the Battalion Quartermaster, Gerald Griffin. Daly was a fine figure of a man with a rather serious looking face and sad dark eyes. In his well tailored green uniform he looked every inch a soldier. The combination of the soldierly figure with the pale complexion and the dark moustache created havoc among the ladies, while his smart military bearing inspired great respect in the minds of the rank and file of the Battalion. Heuston was a violent contrast to our dapper Commandant, a low sized stocky figure attired in a brown tweed knickbocker suit with thick soled boots. He never wore the Volunteer uniform. On the march and even when walking he had a habit of striking down hard with his left foot, as if marking time. The heavy dark eyebrows drawn down in a perpetual frown with the large full lips gave him a somewhat forbidding, almost ugly, appearance, which was quickly dissipated when the rare smile lit up his face, with a clear boyish gaiety. In this he was like Daly as also in that constant calm exterior were concealed depths of great strength and passion. In D Company of the 1st Battalion I made my acquaintance with the source of strength and the mainstay of this new attempt at National Independence - the men of no property - on whom Tone placed his final dependence. Every member of the Company, excepting one, was living on what he earned by manual or clerical labour from week to week. They lived simply, worked well and had curtailed their simple pleasures to provide all their arms, ammunition and equipment out of their own small resources. They were filled with the sense of an impending severe test for which a great reserve of strength would be required and for which they must be fit when it came. They were possessed of a high degree of idealism - but they would have laughed at anyone who ventured to point this out. When not on parade the constant topic of discussion was arms, ammunition and equipment. The acquisition of a water bottle, a belt or an ammunition pouch was an occasion of excited talk and a revolver or rifle or a few rounds of .303 or .22 made the lucky one a source of envy. New ideas on equipment and rations were daily conceived, only to be discarded for even better ideas, few of which ever passed from the ideal into reality. The more practical minded left the problem of equipment and arms to those higher up and had a quiet evening's fun playing spoil five or solo, or in a solemn discussion of a hot tip for the 3 o'clock at Baldoyle being worth the modest investment of a shilling each way. The even more practical smiled tolerantly at the "idea-men" and the gamblers, and made both the butt of crisp kindly wit. There was, of course, the worrier, the Battalion Armourer, who was a member of D Company. His job was to make a Martini take Lee Enfield ammunition or make serviceable some antediluvian type of revolver that had been in somebody's family from ould God's time. The faith in this man's ability and ingenuity was astounding. Of his own limitations he was only too painfully aware, and when his patience was exhausted he used to take refuge behind an explosive protest that "he would be killed by all the work thrown on him before he had time to have a belt at the bloody British."

At this time it was generally accepted that this was what lay behind all the marching and drilling. The parade at Finglas after which Baby O'Connell, then in charge of training, told the Brigade that this would be the last general mobilization until a serious situation should develop, made this feeling more acute. Some, however, interpreted this as a normal instruction at the end of a period of training, and others, more correctly, as part of a general plan to hoodwink the Castle into the belief that we were playing at soldiers - a jibe at us very popular among the west Britishers. To the prevalence of this idea was due the success which attended a great deal of the work done openly under the eyes of the ever attentive and watchful detectives of the G Division, always referred to, in a typical Dublin way, as the G Men. One bright spring evening, Michael Staines, the Quartermaster General, came into the Hall and told me to come with him as he wanted help in moving rifles. I followed him out into the entrance hall where he pointed to some rifles and bayonets, a couple of revolvers and a small parcel of ammunition. He told me to bring them out to a pony trap that was drawn up outside the door of No.5 Blackhall Street. When they were packed in on the floor of the trap he told me to get in and he ordered the driver to start off. As we went down Blackhall Place, Staines mentioned casually that the stuff was to be delivered at Inchicore. At this stage of the proceedings I was not concerned very much, as we looked like a party out for an evening drive. We went along the north quay towards Kingsbridge and having crossed over, went up John's Road. At the Old Man's House, Staines told the driver to turn left and drive through the grounds to come out at Kilmainham. Now the Old Man's House was occupied by the British Army and, of course, there were sentries at the John's Road gate. Immediately I heard the order I thought he had gone crazy, but I kept my thoughts to myself. The driver, however, whose father owned the pony and trap, could not restrain himself and exclaimed: "For God's sake Michael, are you out of your mind, we'll be pinched guns and all. Don't you know this place is lousy with Tommies." A broad smile spread over Michael's face as he replied: "There is not a chance in a million they will suspect us. They will never dream that we would drive through here if we were carrying guns. Go on, smile, and drive past those soldiers as if you were going to the Strawberry Beds at Lucan." Fortunately the driver had sense enough to keep on driving as if nothing was the matter and right through we went without being stopped. As we drove past the sentry and out through the gate at Kilmainham to cross over the back road to Inchicore Staines grinned broadly and turning to the driver said: "What did I tell you - the more openly you do it the less you'll be suspected." On another occasion, having arrived rather early for parade I found Sean Heuston in the hall wearing a brown overcoat which reached almost to his feet. I do not know whether it was his own or if he had borrowed it for the occasion. However, he gave me a small revolver and some ammunition and told me to load it and put the rest of the bullets in my pocket. He then told me to come with him as far as the Broadstone. We set out together, walking along Queen Street, North King Street and up Constitution Hill. No word passed between us until we arrived in front of the Broadstone terminus. We entered the station at the left and when we were at the gate he said: "Keep your eye on me and keep me covered in case anything happens." A train had just pulled in and a party of British Tommies was getting out of the carriages. They threw their kit bags and equipment in a heap on the platform, left their rifles resting against the station wall, and went into what was probably a canteen or refreshment room, leaving their kit unprotected. From where I stood at the iron gate I watched Sean march down along the platform, as if he were on parade ground until he reached the spot where the rifles were leaning against the wall. With a quick look around, he opened his overcoat, whipped up a rifle, put it under the coat, turned quickly around and marched back and out of the station. As he came abreast of me he said, without pausing in his stride, "Come on" and out we went. To the present day I cannot remember what, if anything, happened after that except that when we got back to Colmcille he took back the revolver and ammunition and went upstairs with the rifle. After the Saint Patrick's day church parade and review in College Green, the preparations for the general mobilization at Easter were undertaken with great energy. All the orders from Headquarters published each week in the Irish Volunteer dealing with equipment, rations and arms, though showing an increasing note of anxiety from week to week, created no alarm in either the Castle or the Vice Regal Lodge. The fact that a general mobilization had been held at Easter 1915 and that other activities were advertised openly in the columns of the Irish Volunteer for after Easter 1916, helped to lull the Government into a sense of security out of which they were not awakened until a considerable length of time after the first shots were fired in 1916. When Holy Week came the intensification of activity in moving equipment and its apparently indiscriminate issue, particularly of arms and ammunition, created a feeling amounting to conviction that something serious was afoot. The usual Company parade was held that week without any special comment from the Captain, Sean Heuston, but, Good Friday and Easter Saturday brought with them a hectic time. For some reason best known to himself, Sean had considered me a suitable candidate for the position of Company Quartermaster and I had been appointed to this post towards the end of 1915. What meagre reserve of ammunition and equipment the company possessed I kept in Kane's of Stoneybatter where I had an interest, other than a martial one. Friday and Saturday were spent with Frank Cullen and a handcart, collected God knows where, gathering trenching tools. My family lived then in Lower Gloucester Street near the Convent and on the opposite side to the Carpenters Hall. One of the many journeys we made took us to our house, where in a tool house in the garden at the back there was a good supply of shovels, spades, pickaxes, crowbars and other tools. These were gaily commandeered and transported in the handcart to Skippers Alley to the Fianna Drill Hall. On the last trip on Saturday I stripped a good woollen blanket off my bed without a by your leave to my mother and left it with my rifle and equipment in Kane's. It was great fun and so I did not mind very much the fatigue and sweat caused by the unwanted exertion in the warm Easter sunshine. Towards evening Michael Staines came into Colmcille, and finding us there told us to come with him to No.6 Harcourt Street and bring back some equipment he expected to get there. On the way over Frank Cullen drew my attention to Michael's physical condition. He looked as if he would drop dead in his tracks and bore all the marks of a very much overworked man. We waited in the room at the back of the ground floor and after a while he came back looking very angry. He said: "The stuff is not here, so you two better be off back again to Blackhall Place". After my tea on Saturday I returned to Colmcille and found Sean Heuston there. He told me he had heard there was a rifle, ammunition and a complete British soldiers kit to be got at Usher's Quay and asked me to come with him to help him carry it back. In a lane behind Ganly's we found a young lad about eighteen dressed in khaki and sitting huddled up beside a roaring fire in the front room of a small house. He looked the picture of misery and his uniform was still mud stained. He told us he was going to desert and wanted to get rid of his equipment. Sean handed two pounds to the woman of the house - obviously his mother. We got a Lee Enfield and short bayonet, a set of web equipment with the pouches full of 303 clips and a snipers canvass sling similarly stuffed with 303. We shook hands with the woman and the boy, and wishing him luck returned to Blackhall Street. On the way back Sean gave me two pounds and said that is all that's left of the Company funds you had better take charge of it, we may want to buy food on Sunday. I dumped the stuff in Stoneybatter and later went home to bed. Coming out from early mass in the Pro-Cathedral I bought the Sunday Independent and read the now famous countermanding order by the Chief of Staff, Eoin MacNeill. On my way home I met Garry Houlihan just outside our house. He was very excited and in reply to my question as to what it meant, said he could make nothing of it. He asked me to go to Sean T. O'Kelly's house in Rutland Street to see if there were any orders and to let him know what they were. I went to the house at the end of Rutland Street, near Charles Street and knocked several times on the hall door, but got no answer. As there was no sign of any life in the house I returned home and eat my breakfast. It is highly probable that P.H. and Willie Pearse were in the house at that time, and that those inside would not let me in, as I learned later that it was here the brothers Pearse spent Easter Saturday night. After breakfast, full of curiosity and puzzled beyond words, I went over to Battalion Headquarters at Blackhall Street. Here there was an atmosphere of great excitement and futile speculation, a great deal of criticism of the Chief of Staff and no orders. Eventually, sometime about midday the word was passed round to stand to and wait for orders but no one was to leave the city.

Seeing no point in hanging around the Hall I went to Kane's for my dinner. As the weather was fine, after dinner I went for a walk in the Phoenix Park with Johnny Byrne of ‘A’ Company and his wife. After tea we went back again to Colmcille for the usual Sunday night Ceilidhe. Whether it was due to the general air of excitement in city that day or not, the dancing that night had a dash about it that was not usual. The rebel songs too were sung with greater defiance and the choruses made the roof ring. Towards the end of the night's fun, Michael Staines came into the Hall along with Sean Heuston and asked for volunteers for a night guard on the Hall in case of a raid, as there was a supply of home-made bombs in the back drawing-room. Frank Cullen, Dick Balfe, Liam Staines, Eddie Roach, Joe Byrne and myself were selected, and ordered to go away with the rest of the people in the Hall when the Ceilidhe was over, but to come back later and come in through the back entrance, having made sure that the G man was not about. We all knew 84 D to whom the job of watching Battalion Headquarters was allotted. Cullhane I think was his name, a big soft featured brown eyed west of Ireland man who lived in the Oxmantown area with whom we were on the best of terms and from whom in some mysterious way we got the impression that he was more on our side than he was on that of his bosses in the Castle. Wherever he was that night it was not outside Colmcille because in response to the usual question: "Did anyone see 84 outside", the answer was "no". After the usual joking and codding about we lay down on the floor alongside the paint-can bombs and prepared to sleep. Just before lights out, Sean Heuston came in and joined us. He examined a huge German Mauser pistol and having satisfied himself that it was in working order switched off the lights and lay down with us. It was not long before I fell asleep. Part 2: THE RISING Towards Monday morning, we were all awakened by a loud knocking on the hall door. Immediately the thought flashed into our minds that it was a raid. Someone went to the window and opened the shutters, only to be ordered by Sean to keep quiet and get ready. He cocked the Mauser and told us to stay where we were that he would answer the door himself. He left the room and we remained where we were holding our breaths in an effort to hear what was happening. But strain our ears as we might we could hear nothing. The expected challenge and shots did not come. There was just silence. After what seemed like an eternity the door opened and in came Sean. He had a piece of paper in his hand and his face was flushed. "You may all go back to sleep" he said quietly, but added "I'll want a couple of you to go to Liberty Hall at eight o'clock this morning to act as dispatch carriers." With that we all laid down and I went asleep, what the rest did I don't know. The next thing I remember was being wakened by Michael Staines. We adjourned to the room over the back of the stage, and washed our faces and hands and from somewhere tea and bread and butter and boiled eggs were produced for breakfast. As we sat eating Staines took a black covered notebook out of his inside pocket, handed it to me saying: "Will you keep that for me. I don't want it to be found on me". I put it in my pocket and forgot it. The egg I got was hard-boiled, and was no sooner down than it made me ill. However, I got no time to be sorry for myself for Sean ordered me to go to Liberty Hall, and when I had collected and delivered my dispatch to report back to Colmcille. The city was very quiet as I cycled along the quays to Beresford Place. The weather was fine and the sun was shinning and the usual Bank Holiday air of quietness hung over the city. When I got off the bicycle at Liberty Hall, James Connolly was standing on the steps. He was dressed in the olive green uniform of the Citizen Army. His hands were clasped behind his back and as he looked straight across at the Custom House he rocked gently back and forth on his heels. He seemed without a care in the world and I would not like to have to swear he was not humming a tune under his breath. I dumped the bike in the hall and went up the staircase and waited on the landing at the top. There was a slight amount of bustle, and coming and going into the long corridor on the right which leads into the rear of the building. Some of the men were in uniform and some of the women wore aprons. There was nothing to indicate that within a few hours, in the name of God and of the dead generations from which she received her old tradition of nationhood, Ireland would I was not long on the landing when P.H. and Willie Pearse, both in full uniform complete with swords, dismounted from brand new green and gold enamelled bicycles outside. Without a word to Connolly they passed in and up the stairs, taking the bicycles with them. They too disappeared down the long corridor. Shortly afterwards Commandant Thomas McDonagh, in complete uniform came out from the corridor and asked me if I was from Heuston. When I said yes, he handed me a message and said: "Take that to the address on it, and get a receipt for it. When you have delivered it report back here." It was addressed to Liam Tannam at 3 Wilton Terrace on the canal at Baggot Street. No sooner had I knocked on the door at Wilton Terrace than it was opened by Liam. I handed him the dispatch and told him it was from Commandant McDonagh, and I wanted a receipt for it. He opened it and read it and said: "Read it yourself, while I write the receipt." The message it contained was short - 'Dublin Brigade Order/Headquarters/24th April 1916/1. The Four City Battalions will parade for inspection and route march at 10 a.m. today. Commandants will arrange centres. 2. Full arms and equipment and one day's ration. Signed: Thomas McDonagh, Commandant.' Well, there was something doing at last. There was an end to the uncertainty of Sunday. Whether it was a route march or a rebellion I did not know. I had a feeling it was something serious - more serious than a route march, but what I could not determine. I took the receipt from Tannam and mounted the bicycle intending to go back to Liberty Hall. About halfway on the way back I changed my mind as a number of incidents of the past few days came back to me, and I realised that this was no route march we were going on today. The mysterious message Liam Staines had been sent on down the country and his refusal to tell why, where or what he had gone about. Larry Lawlor's story of having the job of erecting a flag-pole in St. Enda's, Rathfarnham, for the Easter mobilisation. The meeting of Quartermasters called for Blackhall Street during Holy Week. The comparatively free and easy distribution of rifles and revolvers and ammunition the previous week in contrast with the strictness before that. The corner of the room upstairs in Blackhall Street occupied by a motley collection of cans with fuses a few inches long sticking out of them. The notebook Michael Staines had given me that morning. Tom Kelly's statement in the Corporation the week before of the discovery of the Castle plans to suppress the volunteers. That was it. They must be going to round us all up. Well, if there was going to be a scrap I'd prefer to be in it with those I knew and who better than the members of D Company. Impelled by the urgency of this thought I disobeyed orders and deciding to by-pass Liberty Hall headed for Blackhall Street. Passing by Whelan's on Ormond Quay I saw it open and went in to find out if he had heard anything. Whelan's little shop was a kind of information bureau where you dropped in for your rebel papers and cigarettes, and discussed the situation. Whelan was behind the counter and he told me he had been knocked up very late on Sunday night with the news that the Privy Council was then meeting in the Castle, and he had sent the messenger to Liberty Hall with the report that the Castle was going to move against us on Monday. When I told him that we were mobilising for a day's route march, he agreed that things were very serious, but that as we had information about their plans the Castle authorities were bound to be outwitted. As he had no other news I left and went on to Colmcille. Here there was great activity, and Volunteers were coming and going like bees in a hive. Sean Heuston was coming down the stairs as I entered the hall. He called me and told me to mobilise two members of the Company who were excused parades. One lived on the Phibsborough Road and the other in a row of cottages behind Dominick Street, and backing on to the Kings' Inns. The mobilisation orders delivered I returned to Blackhall Place and was told to parade with the rest of the Company at the junction of Hardwicke Street and Temple Street, near St. George's Church. Leaving my bicycle in the Hall I went to Kane's of Stoneybatter to collect my equipment. I put on the complete web kit we had bought from the Tommy in Usher's Lane including his knapsack which had been packed and was ready. I put the Lee Enfield on one shoulder and my own Martini rifle on the other, and carrying my own kit and a spare haversack full of 303, as well as a long French bayonet, I set out for George's Church. Just outside Kane's I met 84.D. He grinned at me, said "Hallo" and passed on. As I went down Stoneybatter the cars were already racing along it on the way to Fairyhouse. In North King Street and Bolton Street the usual Bank Holiday atmosphere was noticeable, but not a sign of a policeman. When I reached George's Church there were only eleven members of the Company out of a possible thirty six, standing on the south eastern corner of Hardwicke Street, in the semi-circle that faces George's Church. Soon after Sean came round from Dorset Street wearing a Sam Browne belt over the same old brown tweed suit of knickbockers wearing a green Fianna hat that was a size too small for his head. It made him look slightly ridiculous and we could not but smile at him. He was completely undisturbed and without any delay gave us the orders to fall in. Jimmy Brennan, Sean Derrington, Liam Derrington, Joe Byrne, Eddie Roach, Frank Cullen, Willie O'Dea, Thomas O'Kelly, Dick Balfe, Liam Staines and Willie Murnane, with Sean Heuston and myself, thirteen men in all of D Company, and Sean MacLoughlin of the Fianna, a total of 14. We marched down Temple Street, Hill Street, Gardiner Street and into Beresford Place. Heuston halted us facing Liberty Hall with our backs to the massive stone pillars that support the railway. He put us at ease and crossing over went in to Liberty Hall. Right opposite to us, in front of Liberty Hall, facing out to the Custom House, two long files of men were standing at ease. The first part of the double file resting on the Eden Quay corner was made up of the Citizen Army, most of them in the olive green uniform with black leather equipment and dashing slouch hats turned up at one side in a very jaunty way. The soldierly effect of the uniform and bearing was spoiled by blue check cotton haversacks which some of them carried across one shoulder. The sling was too long, and the sack shaped like a pillow hung halfway down the leg. They had what seemed to be a large number of the now famous Howth Mausers, supplemented by a sprinkling of double barrelled shot guns. The end of the olive green line was continued by two similar files of men in civilian clothes. There were not so many rifles in this lot, the shot gun predominated, and I have an idea there were what looked like pikes or lances. The tranquil air of Beresford Place of a few hours ago was gone, to be replaced by a feverish bustle. In the background some women were to be seen coming and going in and out of Liberty Hall. In the foreground, civilians wearing shoulder straps and haversacks, some on foot, others on bicycles passed back and forth across Beresford Place over Butt Bridge, down Eden Quay or Abbey Street. In the midst of all the bustle a motor cyclist sat calmly waiting with his feet on the ground and his engine silent. As I thought to myself: "If we look like those fellows we must be a sight", somebody remarked: "That must be the crowd from Larkfield". Another voice said: "No, they are Fourth Battalion crowd," but before a decision about their identity or their appearance was made Sean came down the steps and over to where we were still at ease. He looked very pleased about something, but merely brought us to attention, formed us into fours and putting himself at the head gave us the order: "Quick march." We crossed Butt Bridge and wheeled right onto Burgh Quay. Just past the Tivoli we saw Ignatius Callendar on the footway going towards Tara Street. Ignatius fell in beside him, on a sign from Sean, and after a few minutes conversation while still on the march, he fell out again and we left him behind. There was silence in the ranks as Sean lead us along the south quays, but there was a tremendous amount of speculation going on in our minds about our destination. We had passed Parliament Street, and were abreast of Adam and Eve's before anyone spoke. We had been watching the back of the silent marching figure at our head since we left Beresford Place for some sign, and listening as we approached each corner for the order to turn left or right. But none came. About here we were joined by two members from C Company, Fred Brooks and George Levins. When Skipper's Alley was left behind curiosity got the better of us, and although we were marching to attention we began to question each other as we marched. We were getting very near Battalion Headquarters now, and someone said: "This is all a bloody cod, we're going back to Colmcille, the damn thing is off again". This evoked the reply: "What the hell could this small bunch do anyway, there is not a quarter of the Company on parade, thanks to that ould cod McNeill and his countermanding order". From behind, a fairly audible murmur of conversation showed that the same topic was being discussed, but still no sign came from Sean. By this time we had passed Church Street bridge. and it really did seem as if we were going back to Blackhall Street to be dismissed. “Its all off now” I remarked to Sean Derrington who was beside me. He denied this vehemently and I replied “We would be daft to try anything with such a small number, we would be committing suicide, why, we would be wiped out in a few seconds the odds are so great against us”. Very likely at what he considered a case of funk on my part he snorted in disgust, said nothing and our march continued. As we approached Queen Street Bridge I became more certain we were heading for Blackhall Street, and a dismissal, but as we came abreast of the Bridge no order came from the still silent marching figure in front. We were now on Usher's Island and our bewilderment was intensified. Could we be headed for the Kingsbridge, I thought. In despair I gave it up and marched on with the rest until we were abreast of the Mendicity. Just then Sean turned right about, faced us and shouted: "Company left wheel, seize this building, and hold it in the name of the Irish Republic". At once our pent-up feelings of bewilderment and frustration sought relief in yells and cheers and with a wild rush we went in through the open gates up the stone steps and in the front door. I have no recollection of getting any other orders, but in some way I found myself in the caretakers living quarters on the top floor. Along with me were Lieut Willie Murnane, Dick Balfe, Liam Staines and Eddie Roach. A miniature riot broke out in the front room facing the river. The furniture was manhandled into the windows, the glass was smashed out of the frames, the long cloth curtains were ripped down off the poles and stuffed in between the sashes and the furniture to act as sandbags. The china ornaments, vases and a glass case of stuffed birds were broken in the fireplace to reduce the chance of wounds from flying fragments. Water was brought from some place in a bucket in case of fire. Everything in the nature of cloth in the room was stuffed into the barricade at the window and anything likely to burn was jammed into the fireplace. In the midst of all this shoving and pushing, a woman's voice screamed inside the house while from the back came hoarse cries and angry shouts as the unfortunate down and outs, denied their chance of their midday meal, were being hustled out of the basement dining hall, across the courtyard at the back and into Island Street at the point of the revolver. The slamming of the large wooden gates cut off their angry vocal protests. Dick Balfe then said: “We'll hold this room, Liam you and I will take this window", pointing to the second one from the end of the house, "and Eddie Roach and you take that one" he said, pointing to the end window. Breathless, mostly from excitement, I stripped off my equipment except the snipers pocket and sat into an armchair turned sideways to the window. As I wiped the sweat off my face I looked out through the window and there, with his elbows resting on the stone plinth of the front wall, was a tall D.M.P. man. Under the dark blue helmet, with its silver facing, there was a big soft face with big eyes like those of an oxen. His big mouth was wide open with astonishment and you almost heard him say: "What's the world coming to". After a minute he raised his voice and shouted in a broad country accent: "Eh, you fellows are going too far with this playing at soldiers. Don't you know you can be arrested for what yez are doing". The unconscious humour of this remark struck me as very funny and I burst out laughing. A voice from some other part of the building shouted: "Be off to hell out of that, if you don't want a bullet in your thick skull", but, without effect. He stood where he was seemingly incapable of movement. Again the same voice shouted: "You big ejit, why don't you take yourself off while you're alive. Don't you know the Republic has been proclaimed and your bloody day is done", and punctuated his remarks by firing off a round. The sound of the revolver shot galvanized the Peeler into action and he shot off down the quays so quickly that his helmet fell off his head. I was still laughing when Heuston came into the room. He inspected the barricading of the windows, and then told us that the Irish Republic was to be proclaimed at 12 noon at the G.P.O., and that our job was to hold the Mendicity and engage any troops that would come out of the Royal Barracks across the river in Benburb Street until such time as the 1st Battalion, under Commandant Ned Daly, had taken over the Four Courts and had established itself there. When we got word from Daly that the Four Courts was occupied we were to evacuate the Mendicity and take over the Waiting Room of Guinness's Brewery at the corner of Watling Street in James's Street, and from there to establish contact with Commandant Eamonn Kent who was to take over the Union in James's Street Commandant MacDonagh would be holding Jacob's factory and Harcourt Street, and Commandant De Valera Westland Row and Bolands Mill area. He ordered us back to our posts at the window and said: "When the troops move out of the Barracks wait until they are right opposite to you before opening fire. A single blast on my whistle will be the signal to fire". I turned the armchair with its back to the window, knelt in it and pushed my rifle out through the window using the top of the back of the chair as a rest and waited. The trams were still running along the North Quay across the river, and crowds of people of both sexes and all ages were clustered at the corners of Ellis's Street, Blackhall Street, John Street and Queen Street. Their faces were directed towards the Mendicity, nobody moved along the quays in front of the building. They were waiting for something to happen, and so were we inside the building so intimately associated with one of the most romantic figures of all those remarkable in the history of the struggle for National Independence - Lord Edward Fitzgerald. Quite irrelevantly I remembered I had booked seats for the Gondoliers for that night at the Gaiety, and the contrast between the scented air, the bright lights and the lively music of the theatre and the atmosphere of shabbiness, decay and poverty in the Mendicity, coupled with the grimness of the business that had us here, created a heavy sense of depression that lay on me like a ton of lead. I reviewed all the previous fights for freedom from Owen Roe O'Neill to the United Irishmen down to the Fenians and the consistent failure of each attempt. Dissension and treachery underlay each failure. Informers in some instances, or weakness or division of leadership in others. Sometime the combination of both brought down in ruin and desolation many fair and promising efforts to drive the invader out. This time, however, even if there was dissension at Headquarters, at least there had been no informers. No matter what the Castle had in mind to do against us, we had the advantage this time of complete surprise and had got our blow in first. It rested now with the people of the whole country. If they came over to our side we should be able to pull the job off this time. History, rebellions, insurrections and revolutions had ceased to be that romantic stuff you learned at school or read of in books and argued about with your friends and opponents. We were in a revolution now, and so far there was plenty of physical discomfort, fatigue, sweat, and excitement, but damn little romance. There would be death and blood shed and pain, but it was difficult to visualise what a bullet wound or bayonet thrust would be like in reality, or how one would react to either. The Tommies had reached halfway between Ellis's Street and Blackhall Place, when possibly the strain becoming too much, someone downstairs fired. At that reaction of the rest of us was instantaneous, and we all let go. If Sean Heuston blew his whistle its sound was lost in the thundering reverberations that beat about our ears as the echo of the rifle explosions came back across the river from the houses opposite. The intermittent shooting from the Mendicity now sounded as if each shot had a purpose and a target. From where I lay in the window the rear platform of the tram showed a gap of daylight between it and the roadway and clearly underneath could be seen the boots of the soldiers coming from Ellis's Street in single file into the tram. Through the gap that lay between the rounded roof of the tram and the side could be seen the movement of the Tommy as he crawled along towards the front of the tram. It was just a matter of waiting until he was at full stretch to let one go. The crawling stopped simultaneously with the sound of the shot. While he was being dragged back at the top of the tram the boots under the platform offered a too inviting target and by the time the eyes focussed again on the gap at the top another victim was waiting and got it. Then the space under the front platform presented its sandy-coloured target and you let another go. For a long while this kind of grim triangular target practice went on without a single shot being fired back from the tram as it stood there mute and immobile. Then the sound of a whistle came across the river and the sandy coloured figures withdrew into the side streets, and silence beat down on your head and drummed in your ears. In those first short sharp minutes we had been made into soldiers. The first round was to us. A check up revealed no casualties in the small garrison of 15 men. Murnane had gone out and could not get back, so he joined Daly in the Four Courts. The only damage so far were bullet holes in the back walls of the occupied room, and the window sashes. Leaving some men at each position we began to take stock of our food and to make arrangements for a cook house. The caretakers living room at the back was selected and under Heuston's directions the windows facing towards Thomas Street were blacked out with blankets and a thick table cloth. I examined the sideboard and dresser for food. There was a small supply of tea, sugar and milk, a medium sized plum pudding, a 7 lb bag of rice and one bottle of Guinness. The commissariat dispositions completed I took up my post again at the window, the curious crowds still hung around the street corners opposite, despite the sound of firing coming from nearer the centre of the city. The staccato bark of machine gun fire was now and again punctuated by a deep heavy boom which gave rise to the idea that the British were already using artillery and a slight depression of spirits following on this thought gave place to a great jubilation when someone identified the sound as that of the old Howth gun. It was now very quiet outside the Mendicity, the curious foolhardy spectators were still on the corners; there was no traffic moving and not a sign of soldiers. It was about this time that Heuston sent out Sean MacLoughlin to report to the G.P.O. and to find out how the land lay in the city. Some time after he had gone a squad of Tommies without rifles or equipment, but carrying picks and shovels wheeled around the corner of Blackhall Place onto the quay heading for Queen Street Bridge. We immediately opened fire on them and they retreated on the double back into Blackhall Place out of sight. One or two of them staggered as if wounded. One fell on the corner and was dragged out of sight. The next move against us came much later but this time from Queen Street. Moving out from the Barracks, possibly by Arbour Hill and Queen Street, the British were under cover of the houses until they reached the quay, and so were able to concentrate a large force in Queen Street without the slightest chance of our having a crack at them. We got the first sign of the new moves against us with a burst of fire from a concealed machine gun from the direction of Queen Street. We were down under the cover of the window sills in a flash, and for a while lay there stunned by the appalling din as the machine gun continued to rake the front of the building without ceasing. It seemed as if some giant steel whip was lashing the stone work with a tremendous vindictiveness. Heuston shouted to us to hold our fire, but in truth all we could do was to lie watching the back walls of the room being riddled with bullet holes, and the plaster float around the room in a fine grey mist. He crawled across the landing and beckoned to me to come out. Crawling across the floor on my hands and knees I reached the landing outside safely. We collected a paint can bomb and a candle each, and getting down again on our hands and knees crawled into the long room near Queen Street. We took up our positions, one on each side of the third and fourth windows. The thickness of the walls and the bevelled sides of the windows gave us perfect cover and a slant-wise view of the outside was easily gained by keeping close to the window edge. The giant steel whip was still lashing away, and under cover of the intense fire the Tommies began to rush across the high back of Queen Street Bridge. Heuston struck a match, lit his candle and stuck the long piece of the fuse of the bomb into the flame. He beckoned to me and I followed suit, and there we stood with the bombs under one arm with the fuse in the candle flame waiting for the rush through the front gates which we anticipated was to come. After what seemed like eternity the machine gun stopped firing, and I could then hear Heuston saying: "Don't throw it out until they are in the courtyard". Looking out of the window I could see the round top of the helmet of the first Tommy, who, bent down under cover of the plinth, had come from Queen Street Bridge. When he came to the front gate he jumped across the opening like a rabbit and was gone towards Watling Street. After him came the rest of the attacking force in single file. How many of these rabbits hopped across that opening I could not tell. They seemed to be innumerable, and all the time the fuses of the bombs were in the candle flame, but no sign of them taking fire. At last there were no more hopping Tommies and incredible as it seems even now, nothing happened, and quietness settled down again on the area. The expected assault had not materialised. At this time there were just l3 of us, as McLoughlin had not had time to return. If instead of hopping across the gate they had blown it open and rushed into the courtyard we would have been overwhelmed by weight of numbers alone. Amazed at our miraculous escape, I relieved myself of the weight of the bomb and returned to my post in the next room, thinking to myself, that if the bomb would not blow up it was at least heavy enough to knock a Tommy out if you got him in the right place. There was nothing now to do except keep a look out, and listen to the sound of shooting in the distance; picking out the sharp wasp-like crack of the Lee Enfield and the deep boom of the Howth gun from the waves of sound rolling over the city and announcing to the world that for the seventh time in three hundred years the Irish people were asserting their right to national freedom and sovereignty in arms. The Tommies appeared to have gone back to the barracks, so we examined our rifles, cleaned them and pulled them through. It was getting on towards evening now. After some time we became aware quite suddenly that there was no firing to be heard from the centre of the city. Looking out onto the quay as the dusk began to fall the pedestrian traffic seemed greater and flowing normally, even an occasional civilian passed by on our side of the river. It seemed a very long time since MacLoughlin had gone out to reconnoitre, and he had not come back yet. Just then the tram that had stood abandoned near Blackhall Place since early morning began to move, and to our consternation travelled past us in the direction of the Four Courts - that tore it. If the tram-men were back on the trams and they were on the move again everything must be normal in the city. Daly could not be in the Four Courts. They must have been driven out of the G.P.O. as well. The rebellion must have collapsed. Heuston came into the room to confer with Dick Balfe as to what we should do. He was very puzzled, and agreed that it looked as if this was another fiasco. He asked me how we could get from the Mendicity up to the Marshallsea Barracks, off Thomas Street. Were there any side streets that led onto it from Island Street at the back? I told him there were. You could go up either Bridgefoot Street. or Watling Street. If you wanted you could work your way through backyards of the houses on the south side of Island St. He made no comment except to say that something must have happened to MacLoughlin - he must have been picked up or wounded for he would have been back long ago if not. This failure of MacLoughlin to return seemed to him to be very significant of a complete collapse of the mobilisation, and appeared to help him to decide finally that we had better evacuate. So he told us to clean ourselves up, leave singly and make for home. We were to hide our equipment as safely as we could as it would be wanted again. In the depths of despair we began our preparations to evacuate. I brushed off the fine white powder which covered my clothing, having settled there from the plaster shot off the walls by the machine gunning, and went into the room at the back to wash my hands and face. I was drying myself alongside Joe Byrne when excited shouting was heard below stairs. MacLoughlin had come back. Heuston lead the way upstairs and we gathered round the two of them to hear the news. The Proclamation of the Republic had been read outside the G.P.O. at twelve o'clock, and the Provisional Government was set up there, and was holding out. The Lancers had attacked the G.P.O. and were wiped out. The Magazine Fort in the Phoenix Park had been captured and set on fire. De Valera had taken over Bolands Mill. Sean Connolly at the head of the Citizen Army had captured the City Hall, and the Privy Council which was meeting in the Castle had just managed to escape. Kent was holding out in the Union and McDonagh in Jacobs. We had won hands down, the whole city was in our hands. Ned Daly had taken the Four Courts and the Church Street area, and was planning an attack on the Linen Hall Barracks, and the Broadstone. The Germans had run a cargo of guns into Kerry and were sailing up the Shannon to land troops in Limerick, and march on Dublin. The British had been taken completely by surprise and had been beaten off everywhere they attacked. The Irish Volunteers were now the Irish Republican Army. We all burst out into a yell of delight and danced around in an excess of joy only equalled by our previous excess of despair. We were soon recalled to our senses by a sharp order from Heuston to go back to our posts. As night had fallen by this time the city was in complete darkness, for the street lamps whether gas or electricity were not lighting. As the night wore on the houses opposite and the river disappeared into a black mass. The streets were silent and so were the guns. We talked quietly in undertones in the darkness, speculating on the possible course of events Would the people rise with us and recruits come pouring in to swell our ranks? How many Germans were landed? How much arms and equipment would they bring? So successful had MacLoughlin's story been in its effect on our morale that we were now thinking in terms of how long it would take to establish the Republic all over Ireland. He would have made a great Minister of Propaganda, with his mixture of truth and near lies. Dick Balfe was inclined to be sceptical, preferring to wait and see. Liam Staines was more practical, he was considering the form of Government, and the drafting of a constitution. Eddie Roach was as usual quiet and non-committal. I, in my greenness, was wildly enthusiastic, irrationally sure of success and was thinking in terms of the army as a career. The Irish Army would, of course, be very different from the British Army. Now and again all conversation ceased and we listened intently for the signs of the night attack which some of us felt sure would come. I have no recollection of taking any food nor of making any preparation of food for the rest of the garrison. I have a vague impression of Joe Byrne lighting a paraffin oil lamp in the living room at the back and checking the blackout on the windows to make sure no light shone out through it, and of a kettle of water being filled and being put on the range to boil. What steps I took to satisfy the needs of myself and the garrison - if any - I cannot recall. But one detail stands out clearly still in my mind - the bottle of stout. I fished it out from its hiding place and asked Joe what to do with it, to whom should it be given. He said: "Try Tom Kelly, he is your man, I think he takes a jar and he certainly would be delighted to get one now". I cannot remember if I pulled the cork but down I went with it feeling my way carefully in the darkness for fear I should trip and break the bottle on the staircase. I found Tom sitting beside Jimmy Brennan behind the barricade of furniture at the foot of the stairs. I whispered to him in the dark: "Would you like a bottle of stout, Tom". His reaction was instantaneous: "Oh! the blessings of God on you; this is like manna from heaven" he said, as I put the bottle into his hand. "Be God I could kiss you for this", was his final remark to me as I crept back up the stairs through the rest of the Company who were holding this post. A great deal of my priggishness about drink and those who were weak enough to want it had been knocked out of me. From that moment I was not so much under the restraining influence of Fr. Matthew and the Apostles of Temperance as I had been. Back again to my post at the window to strain eyes and ears into the darkness of the silent city and wait. Nothing stirred about us and not even a dog barked. At length from the direction of Kingsbridge, faintly at first, but getting louder each moment, was heard the unmistakable sound of horse drawn artillery coming towards us. This must be artillery from the Curragh, we thought, the railway line must have been out, and they had to come all the way by road. Excitement had us in its grip again. Here was a chance of a lifetime. They don't know we are still holding the Mendicity, and they are driving straight into a trap. It would be as easy as falling off a log to ambush them and capture the guns. Holy smoke, what a stroke it would be to surprise them and turn their own guns against them - by now it was clear the artillery was on our side of the river. The sounds of the galloping horses the rumble of the wheels and the jingle of the chain traces could each be distinguished. We were on our feet ready to rush downstairs when Heuston came into the room. He ordered us to hold our fire - under no circumstances was a shot to be fired - and to go back to our positions and keep quiet. With a deafening clatter the artillery teams drew abreast of the Mendicity, passed it unharmed and with a scramble of hooves wheeled sharply into Bridgefoot Street. and were gone. We listened to the sounds dying out as they went up Bridgefoot Street towards Thomas Street. As the noise died down, the hope that Daly, as they passed the Four Courts, would do the job, died out. It is a great tribute to the confidence the small garrison had in Heuston's ability that this decision was accepted without question or grumbling. So from then until daybreak the sleepless watch at the windows was continued. Some time after daybreak on Tuesday morning, Heuston carried out a thorough inspection of our position. Out in the courtyard at the back he discussed with Dick Balfe the making of sandbags for the windows by digging up the soft clay in a small garden patch against one of the courtyard walls. He again questioned me about the best way to retreat up to Thomas Street if we were driven out. It was now evident that he was considering the possibility of holding on to his position, although his orders were to hold it for three hours. After a close scrutiny of the side gates and of the backs of the houses in Thomas Street that completely dominated about half of the courtyard and the second and top storey of the building, he announced his decision to partially disobey his orders and try to hold out longer where he was, by telling us that he would send out MacLoughlin to the G.P.O. to bring back reinforcements and supplies. MacLoughlin got his orders. Away with him like a cat over the walls of the houses on the east of the Mendicity into Bridgefoot Street, taking the same route out as he had come in by on Monday carrying a consignment of paint can bombs he had collected from a house in Bridge Street just before the fighting started. The inspection had made it clear, by revealing our weaknesses that, to put it mildly, our position was not a healthy one. The large double wooden gate at the back into Island Street was not barricaded, because there was nothing to use as a barricade, to stem a rush once the gate was blown in. Immediately in front on Usher's Island there was complete cover for bombing parties to take up positions on each side right under the five foot stone wall in front, and lob their bombs in through the open sashes devoid of the wire mesh protection against this form of attack, Although the Mendicity was completely detached from the houses on both sides there was again perfect cover for similar parties provided by the six foot high stone walls of the side passages leading to the rear of the building. Only the width of the river and the two quays separated us from the houses right opposite where an occupying force could establish almost point blank range domination of the front of our position. The second attack of the evening before had shown how easily this could be done with one machine gun. The placing of the Mendicity in relation to the terrace of houses east and west of it presented an ideal opportunity for making it untenable in the front with a minimum of loss. The front of the building we were holding was set back some 36 ft behind the back of the houses on either side. Once occupied by the British it was only a question of punching loopholes in the side walls of each houses and the second and top floors were within 15 ft range of the British fire on the east side and 30 ft on the west side. But such was the confidence inspired in us by Heuston that these observations did not disturb us. That he was aware of this danger on Monday he had proved when he sent Joe Byrne and Jimmy Brennan to occupy a house near the corner of Watling Street after taking over the Mendicity - although he recalled them before fighting started. The quays and the street corners were bare and silent now. There were neither soldiers nor highly unintelligent inquisitive civilians about. Nothing stirred. As the morning wore on the only other evidence of the presence of the British in the area was the sound of hammering which came faintly down to us from the Watling Street side of our position, and the barricade at the Watling Street end of Island Street we had observed from the back gate during the early morning. Speculation about the meaning of the hammering occupied us for some time until as it gradually became more distinct its purpose became plain. The British were working along from Watling Street by punching holes through the houses. Knowing that these houses were unoccupied we realised the British had come to the opposite conclusion and we took great heart from this thought Although from now on an occasional eye went up and down the large expanse of dirty grey stucco of the side wall of the next house on the Watling Street side, in expectation of the falling masonry which would indicate that they had reached their objective, and that we were for it. For the moment anyway there was no other indication of any attempt at another attack by the British. As the day grew older the quiet was undisturbed in the immediate vicinity of the Mendicitv and we spent our time listening to the sound of distant firing in the city. It was some time in the afternoon that we heard the sound of footsteps coming towards us from the Four Courts direction and before long our curiosity was satisfied. We saw a number of Volunteers with an officer in uniform at their head turn onto Queen Street Bridge and with a wild burst of cheering rush across it and up Bridgefoot Street. MacLoughlin had come back with reinforcements. They tumbled in over the garden walls of the houses east of us and in front of them came a British soldier minus his arms and equipment. He had been found in one of the back gardens and was made a prisoner. I rushed downstairs to the back door into the courtyard to open it, Liam Derrington who had been posted in a small room beside the entrance to the courtyard was shouting at the top of his voice: "Come down boys, come down, the soldiers are attacking us from the rear". He was getting ready to shoot the Tommy when he saw the rest of our lads come over the walls into the courtyard and held his fire. There was terrific excitement now. The reinforcements were in charge of Lieut Dick Coleman from Swords and numbered about twelve men from the Fingal Brigade. Heuston soon had them disposed about the building, and the Tommy was taken upstairs to the room at the back. I searched him but found not a thing on him. I cannot recall his name or regiment. He said he was a deserter and wanted to join us. Heuston had sense not to swallow this yarn and decided to keep him a prisoner under guard, so that he could not communicate in any way with those outside. Soon after the excitement had died down I was in the back room with Joe Byrne when I became so overcome with sleep that I nearly fell. Asking Joe to wake me up soon, I laid down and was asleep before my head was on the pillow. When I woke it was dark and must have been well on into the night. Ashamed and furious I remonstrated at being let sleep so long, but to no good. I was told that I looked so tired Heuston had given orders that I was to be let sleep as long as I wanted. Back again at my post at the window and peering out into the pitch dark night outside I noticed that the hammering in the houses west of our position had stopped. The firing from the city had stopped too. About halfway between the back gate of the Mendicity and Bridgefoot Street the Tommies on the barricade at Watling Street opened fire on us. It was a spine chilling sensation, strangely enough devoid of fear, but completely made up of curiosity that we experienced as, doubling along the empty street, we waited the thud of a bullet in the back. We were across the emptiness of Bridgefoot Street in a flash. When we became aware of bullet holes appearing about ten feet over our heads in the distillery wall facing us, a quick look to the rear as we ran revealed that a dip in the road surface had taken us down out of the field of fire from Watling Street We slowed down to a walk and for the rest of the way until we turned into Usher's Street enjoyed the spectacle of the bullet holes appearing in increasing numbers on the distillery wall in front of us. Out on Usher's Quay we made for Church Street Bridge and the Four Courts. Nearing the corner of Bridge Street one of a group of women standing in a doorway called out: "There is two of them. The curse of God on you, its out in Flanders you should be, you bastards - fighting the so and so Germans. Be God if I lay me hands on you I'll tear the guts out of you". As if we were deaf we ignored her imprecations and hurried past, but took the precaution of loosening out our revolvers in our pockets in case she put her threats into action. Our barricade on the Church Street bridge was a nightmare of entangled wire through which we passed after a series of zigzag movements which totalled about six times the normal width of the bridge. We made our way up Church Street into North Brunswick Street and then into North King Street. Turning into Capel Street we went by way of Parnell Street, Denmark Street and up Henry Street to Randall's boot shop. From here we had to pass from house to house to get into the G.P.O. Inside the wax works a figure dressed up in the uniform of the Emperor of Austria stalked around in a parody of imperial dignity to the accompaniment of ribald laughter as he sloped and presented arms with a Howth rifle. Crossing a flat roof to an open window we got into the G.P.O. Those members of the Provisional Government present in the G.P.O. were standing around in the main hall just where the memorial now stands. Winifred Carney sat calmly tapping away on a typewriter on a small table. We reported to Connolly that Heuston was still in the Mendicity and that we had come in for supplies. He got quite excited and gathered P.H. and Willie Pearse, Sean McDermott, Joe Plunkett and Tom Clarke around him. "This is wonderful news" he said, "Heuston still holds the Mendicity. We must send him a special message of praise." He turned to Winifred Carney and dictated the message on behalf of the Provisional Government and signed it. He then handed it to me, and told me to get whatever I wanted for the brave lads in the Mendicity from the kitchen upstairs, and get back to Heuston with all possible speed. Michael Staines took charge of us and while bringing us upstairs enquired anxiously about his brother Liam, and hearing that he was still all in one piece was greatly relieved. Having got our supplies, but before starting back again for the Mendicity I tried to shave myself with a blunt razor. I washed my feet and legs by standing up in a hand-basin fixed to the wall, and feeling refreshed despite the torture of the blunt razor went out again along the roof we came in by. As we made our way down Henry Street and back into North King Street we distributed copies of the 'Irish War News' which had been given to us at the G.P.O. There were a surprisingly large number of civilians moving around in Denmark Street, Parnell Street, Bolton Street and North King Street very likely because things were quiet in this area at the time. As we went past each position and through each barricade messages were called out to us and were returned, and eventually we arrived back at Church Street Bridge. Hands, the confectioners shop in the east side, was occupied as an outpost and making our way upstairs to the front room where a sniper lay behind sand bags we looked over towards the Mendicity to see how the land lay. To our amazement there was a British sentry in front. Our excited enquiries of the men on the barricade and in Hands elicited no information. No one had seen or heard any signs of an attack on the Mendicity and so far as they knew Heuston still held the post. But there was something wrong, that was fairly obvious. There would be no Tommy parading up and down if the Mendicity had not been captured or evacuated. We knew that when Heuston had sent us out that morning he had intended to hold out as long as he was able so he would not have evacuated voluntarily. There was only one possibility, the garrison must have been driven out in some way or other, and were now prisoners or had been all wiped out. Our jubilation of a short time before changed now into a black depression. MacLoughlin decided to scout forward on his own, and told me to wait in Hands until he came back. He made for the Mendicity by way of Hammond Lane. I sat on the stairs waiting and wondering hoping against hope that our fears would be proved wrong. The warmth of my hope chilled somewhat by the cold fact of knowing that Heuston would not have evacuated voluntarily without sending a message to the outpost in Hands to warn us of his new position, and to prevent us walking into a trap in case the British had occupied the Mendicity in our absence. As I sat waiting I became aware for the first time since Monday morning that I was hungry. So I went into the sweet shop and eat some Jacobs biscuits from a tin, and some fruit. Whether I or the garrison had broken our fast up to this I cannot be sure. You can judge of my efficiency as a Quartermaster to D Company when I mention that this is the first occasion I can clearly recall on which I had something to eat since the hard-boiled eggs made me sick on Monday. The garrison of the Mendicity had not had much chance of either food or sleep from the time it was occupied, so constantly had it been kept on the alert. I had gone back to my place on the stairs with a good supply of biscuits and fruit a good while before MacLoughlin came back. He was still puzzled. There was no doubt about the Tommy - he was on duty in front of the Mendicity, and although he had signalled there was no sign of Heuston or the boys in the building. He had not met anyone who could tell him if there had been a frontal attack on the position by the British. We could make nothing out of it. However, he had some of the biscuits and the fruit and went off again determined to find out this time what had happened as another interrogation of the garrison in Hands and on the barricade outside confirmed the fact that they had not seen anything to show that any move had been made against the Mendicity. When some time later he came back from this second reconnaissance I saw at once from his face that there was bad news. It was only too true, the Mendicity was gone. This time he had been lucky to meet a Miss Martin who lived in the Mendicity. From her he had learned that Heuston had surrendered, the garrison had been made prisoners and were last seen headed for the Royal Barracks. There were two stretcher cases, Dick Balfe and Liam Staines, wounded by hand grenades. Queen Street and Blackhall Street were crammed with Tommies and Colmcille Hall was also occupied by them. The hall doorways in Queen Street were crowded with the people from the houses and tea and bread and butter was being dished out on all sides to the Tommies. When someone from one of the doorways tried to draw the soldiers' attention to him by shouting: "There's one of them, the bloody so and sos" he thought it time to beat a discreet retreat and managed to make his way back safely. We sat in gloomy silence for a while - at a loss what to do next. The high hopes that had buoyed us up earlier in the morning were dashed. The wonderful exaltation, derived from the realisation that at last we were free men walking victoriously through the streets of our native city, which had gripped us earlier as we passed from barricade to barricade on our way in and out to the G.P.O. died down in us at the thought of this first defeat, and of the capture of our comrades. The uncertainty of their fate and of their treatment as prisoners in the hands of the British, helped further to increase our depression. We tried to find consolation as we thought of how long Heuston had held out against such superior numbers and that it was ridiculous to think that he could have beaten off such forces. There was nothing to be ashamed of in losing a scrap, particularly under such adverse conditions. Anyway Heuston by holding on so long to his position had prevented the British developing any attack against Daly in the Four Courts for at least three days, if not longer. After their experience at the Mendicity the British would now have a healthy respect for the Irish Republican Army. It was no longer playing at soldiers. Small and all as it was it was going to take more than a few peelers with batons in their hands to wipe it out. When MacLoughlin said: "We had better report to Daly", we got up, left the outposts at Hands, went up Church Street and into the Four Courts. At the back of our minds was the thought that when the British did attack the Courts they would get more than they bargained for, and that we would have a whack at them for Heuston and the garrison of the Mendicity. ************************************************************************************************************************** AFTERWARDS:

summons her children to her flag and strike for her freedom. Nothing, least of all, that sturdy figure in olive green on the front steps, quietly watching the sunshine as it rose, gilding the dome of the Custom House opposite.

Reflection of this kind came suddenly to an end when my eye caught signs of movement across the Liffey on the quays. Incredible to relate the Royal Dublin Fusiliers Regiment were coming out of the Royal Barracks headed by an officer carrying a drawn sword in columns of fours with their rifles at the slope. The column erupted suddenly on the quay and continued to pour its khaki bulk out like a sausage coming from a machine. No advance guard - no scouts thrown out in advance to give warning of enemy forces lying in wait. Stepping smartly in time as if on a ceremonial parade the column came nearer to us, and to add to the air of festivity a tram came running along the tracks from the Park.

I fired with the rest at nothing in particular, and suddenly became aware that I was pulling on a trigger and there was no recoil. I had emptied the magazine of the Lee Enfield in a wild unaimed burst of firing quite automatically and unconsciously. I filled the magazine again, put one in the breech and bringing my eyes into focus I saw that the tram was stopped, and had emptied itself of its passengers. The khaki column had scattered. Here and there in the doorways the soldiers crouched, some could be seen taking cover behind the river wall, others were making sudden jumps for the cover of the tram. The corners still had their clumps of curious and interested civilian onlookers.

That night was quiet and when day broke I went to Heuston and reported there was no food for the increased garrison, except what might have been brought in with the reinforcements, and the 7 lbs of rice, which had been put on to boil in a big cast iron pot of the type then in common use for boiling the pudding for Christmas. He at once decided that I should go to the G.P.O. to bring back as much food as I could get. He called MacLoughlin and told him to go with me. I was to report to Connolly that he was still holding his position, to collect all the information about our positions and those held by the British and be back as soon as possible. Heuston decided that it would be better for us to go out through the back gate. So crossing the courtyard at the double for fear of snipers we gained the cover of the back wall. Carefully opening the wicket gate so as not to make noise Heuston slipped out into Island Street while we kept the open wicket covered with our revolvers. He reported Island Street all clear and out we went. A hasty glance both ways after the wicket gate had been slammed from the inside by Heuston showed us we were the only two people out in Island Street so turning left and keeping in single file close to the wall we headed east along Island Street for the quays, at the double.

My father's manuscript breaks off with the decision of McLaughlin and himself to report back to Daly in the Four Courts.

Wednesday and some part of Thursday were spent on the barricades at Church Street Bridge and East Gate, until they decided to fall back on the G.P.O. On Thursday, P. Stephenson was part of a small force ordered by General Connolly to occupy the Independent Offices in Abbey Street, from which they were recalled to the G.P.O. on Friday morning. Remaining with the G.P.O. garrison until the surrender on Saturday, he was imprisoned in Richmond Barracks from where he was deported on Sunday 30th April to Knutsford Prison in England. Later he was interned in Fron-Goch Camp in Wales, being released in September 1916.

Like many more, he rejoined his company on his release. The fight had only started.

Patrick H. Stephenson

April 1966